Several years ago, I was sitting at a table during a prison ministry training session when the host handed me a slip of paper that read I was driving to the store, after attending service, when I was hit by a red pickup truck as it turned at the corner, and its cargo of green boxes spilled on the street. I was then instructed to memorize the message, put the slip of paper in my pocket, and then whisper the message to the person seated to the right of me. That person, in turn, was to whisper it to the person to the right of them, and so on. It was the classic telephone game. By the time the message made it around the table, it bore only a vague resemblance to the original message.

Understanding how easily messages can be garbled in transmission, the question that every student of the Bible should ask is How can we trust that our copy of the New Testament is accurate, given that it was written 2000 years ago, and how can we trust the Old Testament, given that the stories of Genesis go back over 5000 years?

The beginning of the answer to this question starts with the understanding that followers of the Jewish and Christian faith have historically been fanatical about maintaining the accuracy of their texts, and this is exemplified in the work of the Massoretes: scribes who maintained a particular tradition of insuring the accuracy of scriptures that they copied.

Let’s re-play our telephone game, but this time, using the Massortic processes. Instead of whispering what was written on the slip of paper, copy it carefully onto another slip of paper. Then check it, and check it again. Then count all the words on the original and on the copy. Then count the number of occurrences of each alphabetic letter in the message and compare, then compare the middle character of each word in the message, then check the middle word of the message. As these checks are being done, determine if any single letter is printed either larger or smaller, and if so, carefully duplicate it. Make note of any misspelled words, and instead of correcting them, place a dot above them to indicate that the misspelling was in the original text. If any variations are found in the copy, destroy it and start again. Once the copied message is perfect, hand it to the person to the right, and instruct them to do the same.

Given the new rules of the game, high confidence that the message would make it around the table in tact would be justified. Within the Hebrew tradition, any copy of the Old Testament scriptures that was in error or that began to show signs of excessive wear from use was disposed of ritually. For this reason, the oldest known (nearly) complete copies of the ancient scriptures are relatively new. The best of these manuscripts being the Aleppo Codex (10th century A.D.), the Leningrad Codex (11th century A.D.), the Cairo Codex (9th century A.D.), and the British Library Codex of the Pentateuch (10th century A.D.). Scripture fragments found in the dead sea scrolls, dating back to the 3rd century B.C. show that the text is identical with the text of the Old Testament we have today, with only minor variations such as in Isaiah 6:3 they were calling vs. our current one called to another, and holy, holy vs. our current holy, holy, holy, and in Isaiah 6:7 sins vs our current sin. So after 1300 years, the manuscripts are found to be nearly identical.

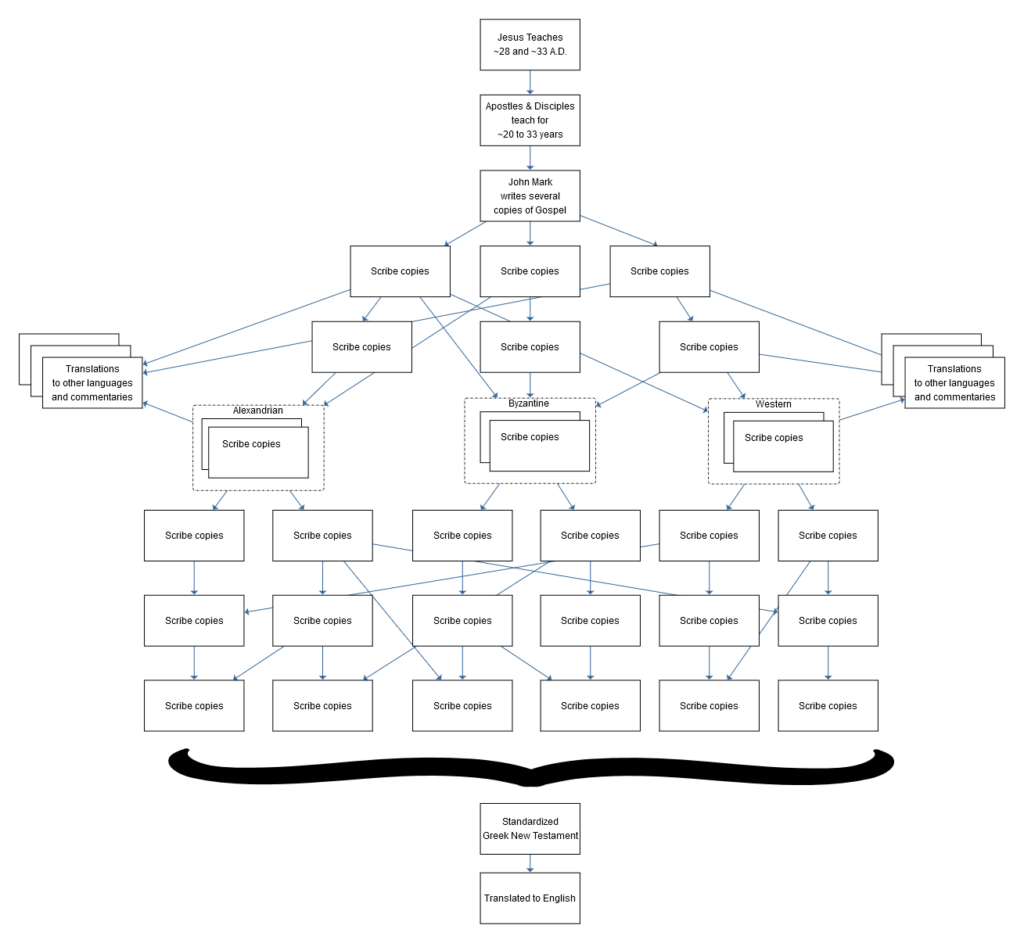

Early Christians felt no obligation to follow the practices of the Hebrews when copying the letters and books of the New Testament, and because of this, scholars have hundreds of copies, and partial copies of these ancient letters at their disposal. The art and science of analyzing ancient documents is called textual criticism, and its traditional goal has been to determine, with as much accuracy as possible, the text of the original autograph. New Testament textual critics, though, are beginning to question if the traditional goal of their profession is appropriate. To understand this, we can describe the more likely process that provides us the New Testament we read today.

Jesus began his teaching ministry in the year 28 A.D. and shared his message in homes, synagogues, fields, and cities throughout Judea, Galilee, Samaria, and of course, in the Temple in Jerusalem. The NASB version of the New Testament captures a record of 31,426 words that Jesus spoke during this time, which equates to about four hours of total speaking time. So what did He say the rest of the time? The answer is twofold. First, He did and said things for which we have no record as John records in his gospel Now there are also many other things that Jesus did. Were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written (John 21:25), and second, it is likely that Jesus shared aspects of His message and parables over and over, just as every modern day evangelist and politician does when on the road.

After Jesus crucifixion, the apostles and disciples went out into the world, spreading the good news of Christ. And like their master, it is likely that Peter, Mark, Matthew, and the other disciples repeated the same stories over and over again in the streets, homes, synagogues, and churches that they visited in their missionary work.

At some point it became apparent to Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John that in order to spread the good news of Christ to a wider audience, they would need to commit it to writing. And although Jesus taught his disciples in Aramaic, the only consistently understood language throughout the Roman Empire was common (Koine) Greek. And so while Greek was a second language to these men, it was the language they chose for their message.

Most scholars believe that Mark was the first to write a gospel, but the specific year has been in debate because of certain references included or omitted from the text. Some believe it was written in the 50’s, while others believe it was written after Peter’s death, between 67 and 70 A.D. A growing idea in the field of textual criticism, is that the authors of the New Testament writings may have made a copy of the writings, themselves, and may have shared more than one copy of their work, conceivably sending out revisions over a period of time. This revelation in the field is what calls into question the defined goal of textual criticism. Historically, it has been to determine, with the greatest degree of accuracy possible, the original text of the writings. But if, for example, Mark sent out different copies of his gospel to different churches at different times, with possible edits to wording and additions in the later copies, what is meant by the original?

We’ll pause the story of the written transmission of the New Testament to consider the spread of the gospel before it was written down. The Book of Acts records that persecution against Jesus’ followers broke out following the stoning of Stephen (Acts 8:1-8), and many of the disciples fled to other towns and countries. Further, many of the three thousand that came into faith at Pentecost (Acts 2) were visitors to Jerusalem from other countries (recall they spoke different languages), where they then returned to spread the message of the messiah, and soon small churches were forming throughout the Empire: all based on the oral teachings of the apostles and disciples.

Understanding how the gospel message was spread in the early days may explain why textual critics have noted that there are more variants in the oldest copies of the New Testament documents than those from later periods: If you were a scribe making a copy of the Gospel of Mark to send to another church, and Peter or Mark, themselves, happen to have taught in your church, in person, you may feel freer to add, or clarify, the stories as you make the copy, based on what was taught at your church.

In the early 20th century, Caspar René Gregory developed a system for cataloging all the known copies of New Testament manuscripts, the earliest of which were all written on papyrus (a paper made from strips of reed grass). The system is simple: whenever archeologists uncover another papyrus manuscript, it is assigned the next sequential number. To date, the last discovered papyri is P140, and a number of the 140 registered papyrus manuscripts date back to as early as the 2nd century.

While papyrus was cheap and readily available in the 1st century, it was, unfortunately, fragile and with age simply crumbles to dust. This is why, in later years, Christians began recording the New Testament writings on more expensive, but significantly more durable velum (animal skins scraped, stretched, and dried), and because of this, history has preserved over 5500 additional ancient copies of the manuscripts. Most of these are copies of only portions of the New Testament, and some are translations into languages other than Greek, but aggregated, provide far and away a more complete textual history than any other work of antiquity. Out of the 5500, three manuscripts have prominence because they are nearly complete copies of the whole New Testament. Dating to the 4th century A.D.: Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus, and from the 5th century: Codex Alexandrinus. With this understanding of the multitude of evidence, a more complete transmission picture of the New Testament emerges, as shown below.

Textual critics have noted an overriding goal, throughout history, in the scribal work of the copyists: that of providing the most accurate representation of the gospel messages. To that end, there is ample evidence that many scribes attempted to correct mistakes or errors in their efforts. For example, since Greek was a second language for Mark, he frequently used singular versions of words in places where Matthew used plural words. Early scribes would attempt to correct, or clean-up the language. Other scribes made limited attempts to harmonize the writings, by adding words or elements from one Gospel to another. Just as English has evolved over time, the Greek language evolved, and some later manuscripts have signs that words were updated to modern variations (the same thing can be seen when comparing the English translations of the original King James version to the New King James version). There are indications that some scribes made word choices to emphasize a particular theological view. For example, to emphasize the virginity of Mary, some versions of the manuscript changed the word father, in Luke 2:33, to Joseph, and the word parents, in Luke 4:43 to Joseph and his mother. One of the most difficult variations is in Hebrews 2:9 where some manuscripts have the grace of God, while others have without God. However, most of the variations are along the lines of the difference in Mark 1:4 where some manuscripts read John came, baptizing and preaching, others read John the Baptist was preaching.

In the early 18th century, scholars began working on a critical edition of the Greek New Testament, with the goal of creating a version of the text that most likely matches that of the original autographs. The latest renditions of this are Nestle-Aland edition #27 and companion United Bible Societies #4 (frequently noted as NA27/UBS4). These critical editions serve as the source material of the modern English language translations we use today. Textual critics use both internal and external evidence when choosing between variants. Internal evidence is based on analysis of the original author’s theology and writing style, an analysis of individual scribes and common scribal techniques, and other considerations such as the possible influence of prominent ideas in later church theology. External evidence considers the age of the document, its provenance, and correlations with other copies that contain the same variants. Scholars have found three primary threads of transmission, where variations were introduced and then transmitted to future copies. They have termed these threads text types, the three prominent being Alexandrian, Byzantine, and Western.

Given the vast number of manuscripts, some known copies dating close to the time of authorship, the fact that most of text, from copy to copy, is identical, and where there is variation, the differences make no difference to the basic understanding of the passage, we can have high confidence that the text we have available to us today is nearly identical to what was originally written by the New Testament authors. In most study bibles on the market, the publishers have footnoted the more significant variations (from the ESV, see Mark 14:59 Have you no answer to make? What is it that these men testify against you? with the disclosed variant being Have you no answer to what these men testify against you?). When variants include whole sentences or passages, they are typically shown within square brackets, as is the case with the ending of the Gospel of Mark (Mark 16:9-18) which is missing from many early manuscripts.

So if we have high confidence that the current versions of our Bible match what the authors originally wrote, does this mean that we can know the exact words of Jesus? Not necessarily, and the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3-12 and Luke 6:20-22) demonstrate this. Both Matthew and Luke recorded the Beatitudes in their gospels, but the wording between the two is different, and there are a number of reasons why this may be the case.

First, as mentioned earlier, it could be that Jesus shared these same basic truths in multiple towns and places, and may have used slightly different wording each time he spoke. Second, psychologists have long known that human memory is malleable–each time we recall and share a memory, the memory gets altered slightly. In the 20-30 years between Jesus ministry, and the actual writing of the Gospels, the disciples almost certainly shared their memories hundreds of times over, so their recollections would have solidified around the wording they, themselves, used to tell the story. Wording that may have been in Greek rather than in the Aramaic that Jesus actually spoke. Third, the gospel writers were interested in sharing the message of Christ, not necessarily in providing a transcriptionally accurate accounting of their experience. That is, Matthew, who was writing to a Jewish audience, may have chosen wording that would convey the truths of the message best for a Jewish audience, while Luke, writing to a Gentile (non-Jewish) audience, may have chosen wording that would convey the truths best to the Gentiles.

This notion can be a challenge for those of us in the 21st century who want to see the evidence for ourselves, but the growth of the church for the first three hundred years following Christ’s death attests to the fact that it is the message (ideas) of the gospel, and not the specific written words of the gospel that impact people’s lives. While individual copies of the four gospels, and copies of the various letters that comprise the New Testament were passed around the churches, the canon of the New Testament (e.g. the official list of 27 books and letters that are considered God inspired) wasn’t fully established until the mid-4th century. During this time, the 120 disciples that huddled in fear after Christ’s death (Acts 1:15) went out into the pantheistic Roman Empire and began to share the good news of Christ orally to all who would listen, and by 313 A.D. monotheistic Christianity was so widespread that it was declared a legal religion of the Roman Empire. It is hard to overstate the unlikeliness of this transformation. During this time, a complete and accurate understanding of the gospel message was elusive for many, because of inconsistent teaching, but in spite of this, God was still able to do a mighty work during this period. Knowing this, we can see that a perfectly accurate transmission of the Bible isn’t necessary for the Christian life.

With an understanding of the variations between different copies of the individual New Testament documents, we can consider, also, the variations between the different Gospel accounts given by Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John. Reading Mark, Matthew, and Luke, it is easy to see that they share many of the same stories, and for this reason, they have been called the synoptic gospels. Some speculate that both Matthew and Luke had copies of Mark’s gospel available to them when they wrote their own. Others suspect that a third document, called simply “Q”, contained a listing of the sayings of Jesus and was used as a source for all three accounts. It seems just as likely, though, that the stories contained in the gospels were the same stories that the disciples had shared orally as they worked together to spread the word to countless followers in the course of their long ministries. It’s the differences between the accounts, though, rather than their similarities that provide strong evidence that the gospels are, in fact, genuine eye-witness accounts of the historical events. One of the more popular and entertaining books discussing this, is J. Warner Wallace’s Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels. In the book, Warner Wallace applied the same techniques he used as a homicide detective in Los Angeles to reveal the likely truthfulness of the apostles’ claims. The minor variations between the accounts, he explains, is one of the best indications that the stories are true. Of further note, is that the motivation of the early Christian writers was non-self-serving. That is, the early writers had nothing to gain by sharing the message that they shared. In fact, they suffered beatings, stonings, shunning, and ultimately execution for sharing their message. They had nothing to gain and everything to lose by spreading this message, unless of course, they were telling the truth.

The historical existence of Jesus is attested to by numerous non-religious sources, and archeological findings confirm the historical accuracy of the gospel accounts in regard to places, customs, and the techniques of crucifixion. Lee Strobel, an investigative report for the Chicago Tribune, provided a very readable discussion of this evidence in his book: The Case for Christ: A Journalist’s Personal Investigation of the Evidence for Jesus.

What remains, though, is to know if the Bible provides us with a spiritually accurate message. Historically, this has been addressed by looking at internal evidence. That is, by looking at what the Bible has to say about itself. The two most referenced Biblical passages used to address this are 2 Timothy 3:16-17 All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work. And 2 Peter 3:15-16 And count the patience of our Lord as salvation, just as our beloved brother Paul also wrote to you according to the wisdom given him, as he does in all his letters when he speaks in them of these matters. There are some things in them that are hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other Scriptures.

Thus, Paul declares that all scripture is God breathed, and Peter declares that Paul’s writings are to be considered as scripture, in addition to the Old Testament. Internal evidence for the spiritual validity (but not historical accuracy) of the Old Testament comes from Jesus himself in that He quoted the Old Testament extensively. The argument is that, assuming Jesus is Lord, then His reference to and quoting of the Old Testament books conveys a heavenly stamp of approval on those books. In fact, He quoted throughout the Old Testament Canon from Genesis 1:27 (see Matthew 19:4) to Malachi 4:5-6 (see Matthew 17:10-11) and from this, the Lord is seen as validating the entirety of Old Testament scripture. Interestingly, many more of His Old Testament quotations appear to be quotes from the Septuagint version rather than the Hebrew version.

In the mid-3rd century B.C., a group of 70 Jewish scholars created a translation of the Hebrew Torah at the request of the Greek king of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, and at the time of Christ, this Greek version, rather than the original Hebrew version, was the more widely available. In general, the textual history of the Old Testament writings is far less understood than that of the New Testament, and so it is significant that Jesus relied on the more readily available version in His teaching, and it is also worth noting that this version corresponds with the Old Testament text we have available to us today.

Setting aside the circular nature of internal evidence (e.g. the idea that we know the Bible is true because the Bible says it’s true), it is important to note that 2 Timothy 3:16-17 expresses an important caveat. In this verse, Paul carefully defines the truthfulness of scripture. He doesn’t claim that it is always historically accurate in the sense that a 21st century news reporter or archeologist might consider historically accurate (see the post on Genre and Historiography). He says that it is profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work. In other words, scripture is intended to address us spiritually, and is not intended to satisfy our unrelated curiosities. This was a mistake the church made when it arrested Galileo for discussing scientific ideas on the structure of the Solar System.

Given that internal evidence of the spiritual truth of the Bible is circular, and therefore, presents an invalid argument, we must look to external evidence. However, seeking external evidence of the spiritual truths of the Bible is ineffectual, because all writings carrying sufficient authority to be trusted were added to the Bible in the canonization process, and thus have become internal. We are left with the same problem that Paul faced when writing to the churches of Rome, which is why he pointed out that the Spirit himself bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God (Romans 8:16), and For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse (Romans 1:19-20). These truths can only be found when we look inward, setting-aside our unreasonable objections. Paul wrote that all scripture is God breathed, a unique phrase without a clear definition, but one that imparts the notion that God was the inspiration behind each of the twenty-seven texts that comprise the New Testament. It’s clear, though, that God is still breathing, and has been breathing His inspiration into the countless scribes and scholars who have taken considerable care in passing along His spiritual truths through the centuries for the benefit of us all.

So to summarize, we have strong, scholarly evidence that the New Testament accounts we have available to us today are accurate representations of the original writings, we have strong evidence that the gospel writers were witnesses to the life of Jesus, we have external evidence from non-religious sources verifying the historical accuracy of the accounts, and we have Jesus word that the Old Testament text we have today is valid for spiritual understanding. And because of this, the idea that the New Testament is just another muddled fairy tale is without justification, and can no longer be used as an excuse to avoid the offer of Christ. The Bible brings a strong message, and ultimately, each one of us needs to choose to accept or deny it. Each one of us needs to accept or deny a faith in Jesus Christ.

For further reading:

Neil R. Lightfoot, How We Got the BibleDavid Alan Black, Rethinking New Testament Textual Criticism

Peter M. Head, Christology and Textual Transmission: Reverential Alterations in the Synoptic Gospels

Michael W. Holmes, The Text of the Matthean Divorce Passages: A Comment on the Appeal to Harmonization in Textual Decisions

Pastor Jeff Riddle, Text Note: Luke 9:55-56

The Synoptic Gospel, How Many Words of Jesus Christ are Red?