This post contains the full text of a talk I gave recently on how to use concepts drawn from electrical engineering and psychology, to gain a deeper understanding of how to go about fulfilling Christ’s Great Commission (Matthew 28:16-20): Go therefore and make disciples of all nations.

I’d like to begin tonight, by talking about the Nyquist–Shannon theorem, also known as the Digital Sampling Theorem, which states that:

In order to accurately reproduce a sound wave-form, digital samples must be taken at a rate that is at least twice the frequency of the sound being sampled.

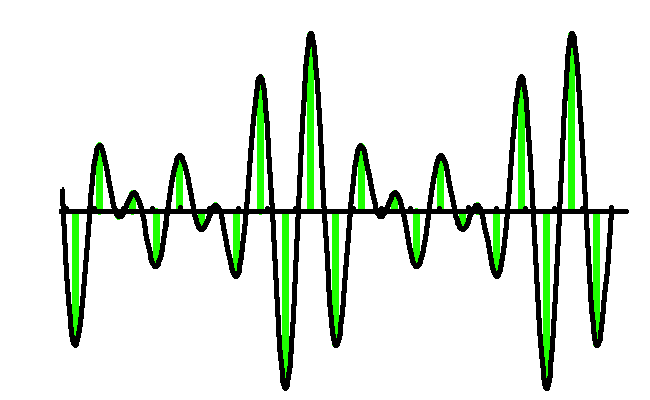

The graph below shows the wave-form of the words Love your Neighbor. (In the graph, the green bars indicate the points where this waveform has been digitally sampled). If sampled at the rate shown (which is twice the frequency), then you will always be able to accurately reconstruct the message Love your Neighbor using the samples taken.

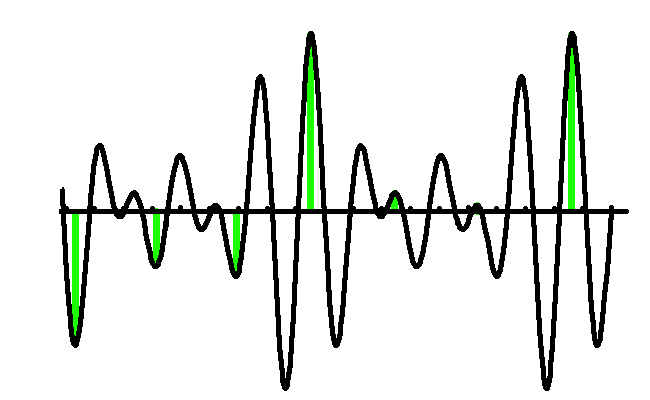

However, if you don’t have enough sample points (note there are fewer green samples in the graph below), and you attempt to reconstruct the wave-form, you might get Love your Neighbor,

However, if you don’t have enough sample points (note there are fewer green samples in the graph below), and you attempt to reconstruct the wave-form, you might get Love your Neighbor,

but you might also get, as shown in this last graph, Love your Neighbor if he loves you first, or even Love your neighbor, as long he keeps his dog off your yard.

but you might also get, as shown in this last graph, Love your Neighbor if he loves you first, or even Love your neighbor, as long he keeps his dog off your yard.

Note that the sampled information (green bars) in this graph, and the one above it are the same, but the reconstructed message is different.

Note that the sampled information (green bars) in this graph, and the one above it are the same, but the reconstructed message is different.

I’m going to jump topics here, so bear with me.

A study was done recently on first impressions. The researchers wanted to know how long it took us to size up someone’s competence, likeability, aggressiveness, and trustworthiness, and so they did some experiments. How long do you think it takes for us to get that impression?

- 60 seconds

- 30 seconds

- 7 seconds

- 1/10 second

Yes – the researchers found that it takes about 1/10 of a second. And they also found that our initial impression doesn’t change much, when given more time.

Do you think 1/10 of a second gives us a lot of sample points? Let me ask you:

- How many sample points do you think it would take to fully understand who a person is?

- How many sample points do you think it takes to fully understand God?

Do we have enough?

I’ve been reading a few books and articles on recent psychology research and what they’ve found is that the human brain has an incredible ability to fill in the gaps. In order to survive, we need to make decisions, and in order to make decisions, we need facts. So our brain does us a favor. When it doesn’t have enough sample points, it simply makes up the missing facts. This is helpful if we are alone in a dark alley: our eyes may see the slight shift of a shadow, and our brain will start screaming Bad guy–run! Where it doesn’t help us, is when we see someone drop one dollar into the collection basket and our brain starts telling us: that guy’s cheap.

As Christians, we need to be aware of the implications of our brain’s behavior. We need to understand that:

- These artificial inferences are pervasive: our brain is doing it all the time.

- We don’t realize that we are doing it.

- We believe the facts that our brain synthesizes.

- This one is key: Some percentage of the time, these “facts” will be wrong. Just as we saw with the sampling theorem–multiple possible explanations can fit a limited set of data points. That guy who dropped one dollar into the basket? He had emptied his wallet into a Salvation Army bucket less than 20 minutes ago, and the basket reminded him that he had one more dollar in his left pocket. But forevermore, my brain knows him as the cheap guy.

The whole collection of beliefs that we have, defines what is known as our worldview. And if we now understand that each of our individual beliefs may be flawed, can we conclude that, to some degree, our worldview is always going to be flawed?

What do you think about the worldview of the white population of Mississippi up through the 1960’s? They went to church and listened to nice talks too.

Here’s a harder question. How will history judge your set of beliefs?

So what I wanted to talk about tonight is not actually the sampling theorem (interesting, as it is). What I wanted to talk about is what the Bible has to say about error.

When I started to think about this, what came to mind is some of the side-stories in the Gospels. Stories about the Pharisees–who spent their whole life trying to figure out how to be right with God by dissecting and regulating The Law. They were wrong. Stories about James and John, who were raised in a prominent, status-oriented family and who brought that same thinking to their relationship with Christ. They were wrong. Martha–who thought that hostessing and hospitality was the most important thing to do when Jesus came to visit. She was wrong. Levi–who thought it was OK to gain wealth, as long as he stayed within the confines of the Law, even though he was extorting his fellow countrymen. Levi was wrong. Judas–as a Zealot, he thought that bringing God’s kingdom required the use of force. Judas was wrong.

What I find disturbing about these stories, is that when I think about how I live my life, it seems clear to me that I have little bits of each of the Apostles’ world views in my own. So I know that there is a problem. Why, after being a Christian for more than 26 years, do I still have a flawed worldview?

To answer that, I’m going to share two more tidbits from the psychology books I’ve read.

Before I do, though, I know that some Christians don’t believe in psychology. So I’ll give you something to think about: As I’ve been reading through, it has dawned on me that recent psychological research might provide some of the best worldly proof of the Bible, because what the researchers seem to be proving is that everything that the Bible says about how to live your life, is true.

Getting back to the tidbit–when evaluating new information, like what I may be giving here, our brain has an incredibly strong tendency to accept, as true, anything that supports our existing beliefs, and reject, as false, anything that contradicts what we already think.

What does this mean? If I’ve been raised in a church that believes that we must do good works to be saved, then I’ll accept any sermon and any verse that supports this view, and I’ll either not pay attention to, or find fault with, any that contradict this view.

Let me give you another, more socially relevant example.

In August of 2014, a white police officer shot a black man in Ferguson, Missouri, and in the hours and days after it happened, a variety of mixed news accounts spread across the nation. Now both my sister and her husband are police officers, and I had heard a number of tales about the challenges of patrolling bad neighborhoods. It was clear to me from the news stories I heard, that this heroic officer was put in the terrible position of having to shoot a violent, and drug-crazed criminal. At the time, though, I was working with two African Americans and I asked them about it. Their response was immediate: that policeman just shot that innocent kid and he’s going to get away with it. In talking further, I found that growing up, they had lots of experience with unjust harassment by police, and they implicitly believed the news story that the police shot the boy as he was trying to surrender.

I, on the other hand, realized that I had implicitly dismissed those accounts. Why? Not because I had any more evidence than my co-workers. It was simply because it didn’t jive with my previously existing ideas of police behavior.

We each accepted the information that strengthened our existing views, and dismissed any that contradicted them.

Think about the implications of this, given that we now realize that, to some degree, our existing views are flawed and incomplete.

The third and final tidbit is this: humans tend to synchronize their beliefs with those around them.

This election season, I’ve seen a couple of articles on this. Pollsters have found that political views can be very cohesive on a state and even a county level. This synchronizing of beliefs also happens within companies, communities, churches, and families. I suspect that this happens because we tend to accept information and ideas from people with whom we have a close relationship.

[This tendency to synchronize beliefs is why, in 1 Samuel 15, God ordered the Israelites to kill all the Amalekites, including the women, and children: He knew that, otherwise, their beliefs would corrupt Israel’s. Jesus’ admonition to beware of the leaven of the Pharisees and Sadducees (Matthew 16:6), was also intended to guard against belief corruption.]

A big part of what we call culture, is that set of synchronized beliefs that a particular group of people have.

So the big question I’m raising tonight is: How should we go about living, as a Christian, knowing that some percentage of our culture, and our worldview is wrong?

When I started to think about this, the first thing that came to mind was my need for a deeper sense of humility. [As a side-note, did you know that up until Christ’s crucifixion, humility was considered a weakness?]

I’ve found that by constantly keeping myself aware that I might be wrong in fundamental ways has helped me to become a much better listener. For example, when I heard people talk about white privilege, my initial reaction was negative, but then I stepped back, and decided to do some in-depth research on the topic, which helped me to see things from a different point of view.

Another aspect of this awareness of error, is that I don’t judge others so harshly when I know that they are wrong. I realize that everyone is trying to make it, the best they can, in a challenging world. Just like I’m wrong sometimes, they will be too.

OK–Here is a bonus tidbit from psychology. Our comprehensive set of beliefs is at the core of our very identity, and our sense of identity is what brings us stability in the world. This is true, even if we don’t like who we are.

The reason that this is important to know, is that when we introduce conflicting ideas to people, we run the risk of threatening their sense of who they are, and when this stability is shaken, there is going to be a reaction.

Let me put that another way: When you try to prove to someone that they are wrong, you’re likely to provoke an obstinate or violent response–and the reason may not be that they don’t like your idea, the reason may be that you are shaking their sense of identity and stability.

Given this difficulty, should we, as Christians, be interacting with people having different belief systems? With different cultures?

The Great Commission says yes. So how?

To get an idea, we can look at the two greatest influences in the Bible: Jesus and Paul.

Have you ever thought about the fact that both Jesus and Paul were raised in multicultural environments? Jesus was raised in Egypt, then moved to a region of Galilee with heavy Herodian influences, and at the same time, was steeped in traditional Jewish culture.

Paul was raised and educated in a Greek town that was controlled by the Romans, and when he was older, he moved to Jerusalem.

Today, our western culture is a mix of Greek, Roman, and Israelite influences, but in Paul’s day, the cultures where more distinct. The Greeks where big into competition and valued personal excellence. When writing to the Greeks, Paul spoke to them from their own cultural perspective: Do you not know that in a race all the runners run, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way as to take the prize (1 Cor. 9:24).

Rome, on the other hand, had two driving cultural influences. Like America, they were big believers in law and order, and at the same time, they were a slave society, with half the population of Rome, and many in the early Roman church, being slave. Many have commented that Paul’s letter to the Romans reads like a legal textbook, and when Paul talks about becoming slaves to righteousness (Romans 6:15-23), we can see that he is connecting to his audience in a culturally relevant way.

In Acts, when Paul addresses the Jews after he was captured, we again see him connecting in a culturally relevant way, speaking in Aramaic and describing his zealousness of God and the scriptures (Acts 21:40-22:3).

What Paul shows us, is that it is possible to set aside the supremacy of our own cultural norms and ideas, and learn, and even adopt, thoughts and ideas from other cultures and other people so that we can connect and serve them, as Christ’s representatives.

I picked up a related thought on this, from a book on Christian Counseling I’ve been reading. In it, the author emphasizes that Christians need to take a broader view of what we call multi-cultural.

Old people and young people have different cultures. There’s blue collar and white collar, inner-city and suburbanite, Apple® users and Android® users.

So again, when we go out into the world, we need to constantly be aware that our assumptions about everything from social norms, to clothing styles, and even to theology, may be faulty and incomplete. Keeping this in mind will help us to be more humble, help us to listen better, drive us to study and learn more, and help us to be less judgmental of those around us. So for Christians, this isn’t really a new message, but hopefully, I’ve given you a new way to look at it.

I should end right here, but I’d like to squish in one additional insight.

I’ve been talking about how an awareness of our brain’s misleading thinking can affect us as we go out into the world. The same awareness can help us when we go inward–when we think about ourselves.

Many of us suffer from depression, shame, and anxiety, and the root of much of this is erroneous thinking. We put two and two together, and come up with the idea that we are valueless or flawed, and because of our broken thinking, we have a hard time hearing any ideas or encouragement to correct us in these beliefs.

If any of you are struggling with these, and we all do from time to time, please be aware, that your brain’s fooling you, and to break free of it, you need to do the same thing I talked about earlier. You need to listen to people with a different perspective. You need to talk with someone.

Again, Christians sharing their lives with each other shouldn’t be a new thought for any of us. Hopefully this will give you a little encouragement to do it.

For those interested in these topics, the following resources may be helpful:

Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error – Although this book (in my opinion) has a subtle anti-Christian bias, it provides a good overview of how error enters our cognitive thought processes.

On Second Thought: Outsmarting Your Mind’s Hard-Wired Habits – Explains how hardwired shortcuts, within our brain, affect our thinking and decision making processes.

The Great Courses: The Foundations of Western Civilization – Describes the distinct nature of Greek, Roman, and Jewish cultures at the time of Christ.